What's New > ‘Voices of COVID’ author Tim Bostwick shares his personal experience

|

Tim Bostwick at the hospital

|

Author of the NATS continuing series, “This Will Be Our Response: Voices of COVID-19,” doctoral student Tim Bostwick interviewed many people in the vocal performing arts industry about their encounters and experiences with COVID-19. In March of 2021, Bostwick and his wife both contracted the virus. Bostwick shares his own story of long-hauler’s syndrome, and how he is coping today.

Tell us about your personal experience with COVID. You contracted COVID in March of 2021, correct? How did this affect your life — both at home and professionally?

To give some background: on March 13, 2020, the fine arts world shook as the pandemic created a wave of cancellations and unemployment. Countless individuals across the globe were suddenly unemployed and sheltering-in-place. The following Monday, I began recording stories from the field for Voices of COVID-19: This Will Be Our Response. But as you mentioned, my personal story takes place a year after that event.

Being a professional singer with asthma, my wife and I took the pandemic very seriously. Our teaching positions at both The University of Iowa and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign moved to digital platforms, which meant we could isolate at home. We also began ordering our groceries for pick up and refrained from eating in restaurants. We didn't travel and tried to be as cautious as possible. However, I have learned that caution can be misleading as it allows us to feel that we control the pandemic. While it's true that we can mitigate risks (while protecting ourselves and those around us), we cannot regulate the virus or who it infects. The myth of control ended for me on March 23, 2021.

On that Tuesday afternoon, my wife and I went to get our initial mRNA vaccine doses—this was when shots were still a rare commodity, so we were both incredibly excited. We drove a half hour to the Tazewell County Health Department and received our injections. My wife had 48 hours of side effects (including a low-grade fever and body aches), while I had nothing but a sore arm. Three days later, on Friday, March 26, 2021, my wife woke with no sense of taste or smell. Within hours, I developed a mild cough. I pushed through until Saturday to give an online talk to the Iowa chapter of NATS about Voices of COVID-19. Immediately after completing that presentation, my wife and I went to get tested. That night our diagnoses came back positive for COVID-19. I remember seeing the email notification and not believing it was possible. But I still had hope that I would only feel like I had a cold because I was young.

Unfortunately, my symptoms kept getting worse. These symptoms included a racking cough, a high fever (103.7+), loss of appetite, and extreme fatigue. Throughout the weekend, my cough progressively worsened, preventing me from getting restful sleep. Yet, the night before I was hospitalized, I remember sleeping soundly. I thought I was recovering and finally getting some much-needed rest. However, the truth was that my blood oxygen level had dramatically worsened. When I could not fully waken on day 6 or 7, my wife noticed a pale blue tint around my lips and fingernails and decided to take me to the hospital. Normal pulse ox readings are above 95%, and we were told to watch if mine dropped below 92%. The last time before we went to the hospital, I was at 88%. But let me be clear, I still thought I was getting better.

When we arrived at the OSF Saint Francis Medical Center: Emergency Room, it was clear that the staff had been dealing with this for a long time. They were not mean but direct. The front desk nurse told my wife that she had to leave, and I won't forget how she looked at me. There was a measure of sadness on her face but a force of will to give me strength that masked it. We parted without saying goodbye, and that's the last time I'll ever make that mistake.

I sat in the COVID portion of the waiting room, which was surprisingly empty at the time. The nurse called me, and I picked up my bag, caught my breath, and shuffled after her. (I was still wearing my slippers because if I had to be at the hospital, I was going to be comfortable.) She took my vitals and showed me to a room where I shrugged off my street clothes and assumed the hospital gown. Suddenly, there was a flurry of activity where I had an EKG, was hooked up to various monitors, and started on an IV. I was also started on oxygen (5L) and given an X-ray that revealed bilateral (both lungs) pneumonia, which is commonly known as "COVID pneumonia." The Attending Physician came in to inform me that I would be admitted to the hospital and started on treatment to help my body repel the virus.

In contrast to the initial flurry of activity upon my arrival, I was held in the ER until a room was available at 2:00 am. Staff was limited due to both a pandemic wave and the infectious nature of COVID. My world shrank and would continue to do so over the next several days as I was admitted and treated. The room I was eventually assigned was larger than what I expected. There was a bathroom attached, and the third-floor window overlooked a section of roof leading to a side entrance, where I saw nurses come and go each day. This room and its window became my world. Due to isolation procedures, I saw nothing of the hospital beyond my room.

Once I had reached my temporary home, I was immediately started on several medications to battle the virus. These included: remdesivir, Rocephin, azithromycin, dexamethasone, vitamin-D, and zinc. Additionally, Lovenox was used for combating blood clots (this was my least favorite medication as it was injected into the abdomen). However, the medication that struck me the hardest was remdesivir because it was the same treatment for former President Donald J. Trump. The gravity of my situation became apparent, as I was treated with the same medications used to save the President of the United States when he had COVD-19. When my delicate health became clear, I felt privileged to receive such treatment in that terrible moment.

During my six days in the hospital (a much shorter time than many Covid sufferers endure), I learned many lessons and would share a few here. First, the nurses, doctors, and hospital staff showed me kindness and strength at my weakest and most vulnerable moments. In one of many examples, I remember struggling to breathe while in the bathroom and having to pull the emergency light so I wouldn't lose consciousness. I made it back to my bed, but the experience cowed me to the point where, for the first time, I began wondering if I would make it. The nurse that rushed in (gown, mask, and face shield intact) stayed even once I was medically stable. She made sure that emotionally I would have the strength to endure. A second lesson includes the unexpected forms that such kindness could take and marks a turning point when I began to have hope. Hospital food is not known for being a culinary delight, and my experience was no exception. Even as I regained my appetite, the quality of the hospital food turned my stomach. One of my nurses offered to retrieve outside food if my wife delivered it to the hospital, noticing my lackluster eating. Though it was such a simple action, her volunteering this service touched me deeply.

I've taken a third lesson from this experience: the vocal performing arts community is fantastic. Even though I was in isolation, I was seldom alone. I received messages and well-wishes from across the globe. Friends checking in on me filled my phone with encouragement and support. For each one of them, I am eternally grateful. Our shared community kept me company in a very dark moment.

A fourth lesson involves fear. I had begun to dread the respiratory therapists' daily visits as inhaler treatments led to uncontrolled coughing fits that left me shaken and weak. When I expressed this fear, the excellent therapist looked at me and said, "Take a couple of breaths, then." This simple directive became my motto in recovery, meaning that when I came up to a seemingly insurmountable obstacle, I did not have to conquer it all at once.

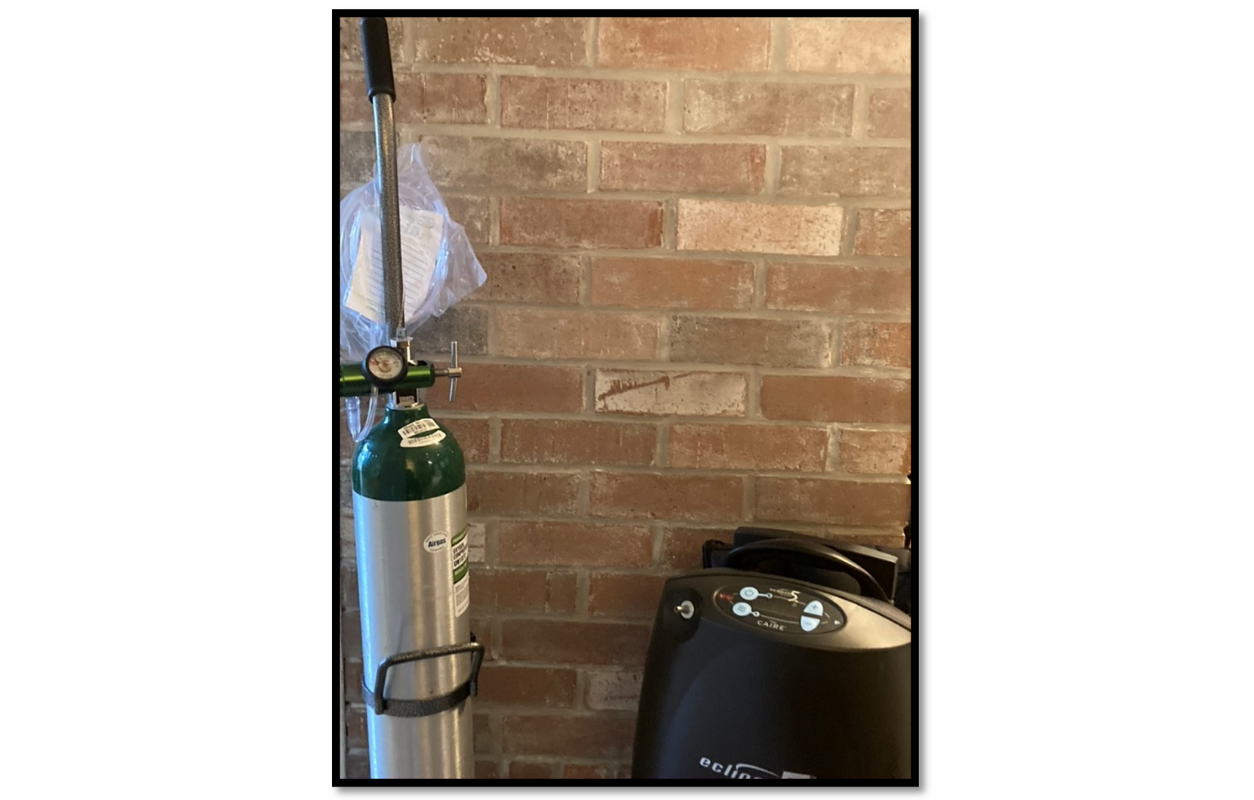

This mantra and motto served me well when I was sent home on oxygen and several other medications on April 7, 2021. But I had no idea how frail I indeed was until I arrived home and had to ascend our single flight of stairs. My wife lugged the oxygen machine behind me step-after-step as I lumbered slowly up the steep incline. I moved slower than ever before, yet I still had to stop and take several deep breaths every couple of steps. I would pause while clutching the rail so as not to fall. At 37, I had never expected such a stark reminder of my own mortality. Yet, I kept to my mantra and celebrated small victories in the days to come, hobbling between our living and dining rooms. As I built up strength, I eventually began walking outside. However, my oxygen levels continued to drop dangerously low occasionally, so we had to monitor it closely. Both my oxygen machine and tank were constant companions until May 31, 2021, when I was able to get rid of them finally.

Unfortunately, the impact of COVID-19 doesn't seem to end with the acute or immediate physical response. In fact, medicine has learned that many people (including myself and my wife) develop long-hauler's syndrome. For me, this impacted my voice and mental state, as I developed Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and anxiety regarding my severe illness, treatment, and the ongoing COVID pandemic in general. As I made progress with my recovery, we experienced a further near-catastrophe. On the morning of November 2, 2021, my wife came downstairs to help me with breakfast and suffered a mild heart attack. This event was completely unexpected, though she had experienced mild tachycardia (a resting heart rate in the 90s to low-100s) since her COVID infection in the spring. My wife is a vegetarian with no risk factors and was only 39 years old, so we almost couldn't believe it at first. She spent three days in the hospital and had several tests to confirm the event. An angiogram ruled out blockages and structural abnormalities. The only explanation doctors can give her is that she has long-hauler's COVID-19. What this means in the coming months and years remains unknown.

Despite the health difficulties surrounding our experience with COVID-19, we count ourselves lucky. In perspective, over 800,000 individuals in the USA have passed away, and the mental health toll on health care providers is unparalleled.

After being so careful and talking with others about their experiences, how did you and your wife feel about contracting COVID-19?

I think that is a crucial question. And even more broadly, how do we as a society feel about the continuation of the virus? At one point, the forecast of 250,000 fatalities to COVID was unthinkable. We are currently around 850,000 American fatalities and experiencing a surge in COVID cases. While the pandemic may be unprecedented in our generation, our complacency and acceptance of these numbers is worrying. I hope that when we emerge from COVID, it will be with a deepened sense of empathy for one another. Sometimes that means putting the needs of my neighbors first, even in the face of inconvenience.

Back to your original question, my wife and I are optimistic realists, which means we expected to become sick at some point, though perhaps not this sick. During my hospital stay and after, I was asked if I believed in the virus or the vaccine several times. It is difficult not to feel a moral judgment about having COVID, especially so severely. But the virus is not political. Anyone can be infected. Everyone is potentially at risk. That means I can't feel bad about having caught the virus, nor the fallout from it. Frankly, it has taught me how beautiful my communities are, even at the darkest times. I hope never to forget the lessons of humility and grace that I have learned through this experience.

I am also lucky because I could get treatment and didn't have to wait more than 8 or 10 hours. If I had been insured or couldn't afford my medical bills, perhaps I would have delayed or refused to go to the ER when my wife insisted. One day could have made the difference between needing a ventilator or not. What if I lived in a different country? What if I didn't have access to an oxygen machine? I don't know, but I am glad I didn't find out.

Let's talk COVID and singing for a minute. We know that there can be all kinds of repercussions on the voice. Did you experience issues yourself? How are you doing today in regards to your voice health?

Yes, there are two large-scale issues with singing which I will address. The first of these is breath. There was undoubtedly short-term damage to my lungs from COVID-19. At its worst, my pulse ox in the hospital was 87%, and once at home, it lingered around 92-96%. Obviously, this impacted my breath's longevity both in singing and speaking. I found that I would awkwardly breathe in the middle of a sentence or need to stop talking to catch my breath even while speaking. These issues are less prevalent today, but occasionally I still see issues and have to remind myself of my motto: "Take a couple of breaths."

On June 7, 2021, my second vocal issue was confirmed. I was diagnosed with vocal nodules by Dr. Johnson of Peoria Ear, Nose, & Throat. I can't describe the difficulty that accompanied this diagnosis. I remember sitting in the office in stunned silence as Dr. Johnson gave me the news. My voice had always been a trusty, dependable friend that I could rely upon over the years. It was always there for me. Suddenly, my voice was a casualty of COVID-19. Thankfully, I was able to take a much-needed period of vocal rest, and six months of relative silence was just what my voice needed. With rest and coaching from a Speech-Language Pathologist, I was cleared from vocal nodules on the same day my wife successfully defended her dissertation. On December 13, 2021, we celebrated both our triumphs and began looking forward to a hopeful holiday season.

You've mentioned that you've dealt with panic attacks and flashbacks related to this trauma. Are you still experiencing them, and how are you coping?

Yes, as I mentioned before, I was diagnosed with PTSD related to COVID and my treatment. But I don't think that my position is altogether unique. We have all experienced a collective trauma associated with COVID-19 and are still in the midst of it. If you watch a TV program and catch yourself thinking, "Shouldn't they be wearing a mask?" you have absorbed the new reality. Mine just happens to have a bit more teeth.

Usually, they come as small reminders of my stint in the hospital that trigger a more significant event. The first incident was triggered as I was going up the stairs. I was innocently ascending the stairs when I flashed back to that first night home from the hospital. I entered a loop that left me breathless, trembling, and troubled for hours. However, because of my research and work with Voices of COVID, I don't anticipate getting away from COVID-19 soon. So, I looked for treatment that involved immediate relief and long-term results, which led me to specialists in behavior therapy and psychiatry. For my longer-term needs, I began the process of training Lift. She is my four-month-old Aussiedoodle puppy that is becoming my service dog. She is brilliant and has already started to alert me when I am disassociating or beginning to have a panic attack. Even as I write my responses, she is here at my feet.

What do you feel is the biggest takeaway from your experience?

COVID is a defining moment for our generation. The fabric of our industry and culture has been forever altered. We don't have the option to "get back to normal." There is no normal. There is only innovation, and we have seen that in our world and the vocal performing arts. For instance, who knew we would become proficient at teaching via a video platform?

As I mentioned before, I hope that empathy is the main lesson that we take away from the COVID-19 pandemic. There are many ways that I was shown empathy during this past year, so now it is my privilege to provide that same understanding to others.

We are rooting for you and your wife, Tim! Thank you for sharing your experience and story. We hope it helps others who may be dealing with long-hauler's syndrome or unresolved problems from COVID feel like they are not alone.

To end on a lighter note, did you watch a lot more television in 2021 than ever before? If so, are there any shows (or any media really) that you have enjoyed and would recommend?

My wife and I love binge-watching established tv shows; the more seasons, the better. Our top recommendations are The Great British Baking Show, Doctor Who, and (of course) Schitt's Creek.

Read more about Tim Bostwick and browse the “Voices of COVID” interviews in the NATS collection.